When one considers the scope of all these blog assignments, from the beginning with an analysis of the media’s role in the Haitian cholera outbreak to the application of film theory to a foreign piece of cinema, the overall goal would appear to be a synthesis of anthropological media theories and an application to specific cases, contemporary and otherwise. Thus, the end result should be a collection of analytical articles on specific media issues using new scholarly knowledge from course materials and our own creative/critical skills. Looking at two blogs from my peers, Riaz Makan’s and Eric Fontaine’s, we can assess their final contributions to the field of media anthropology through the writing of their respective case studies.

Eric Fontaine’s class blog (http://ericfontainemediameditation.blogspot.com), takes a rather personal slant on most the assignments as he seeks to color the scholarly theories and contemporary issues with some of his own, more anecdotal experiences. Such an approach, while not strictly scholarly, makes a valuable contribution to the field, nonetheless, as it provides a distinct, personal take on issues that are usually addressed in more academic means. He does a good job in all his articles of summarizing the key points made by other scholars on the topic at hand. For example, interacting with writers such as Walter Benjamin (in the “Jai Ho” post) and Jaques Lacan (in the film theory post ) in order to provide an academic/critical framework within which he may further discuss the specific cases. Unfortunately, many of these did not go far enough to draw his own opinions together with the academic views on the issues at hand. They are often merely paralleled without an enough critical linkages being made between the scholars’ theories and his own anecdotes. His best developed posts, such as the graffiti based assignment (“Graffiti: you are what you write?”) do develop such interplay and, indeed, perform a strong analysis. Specifically he draws upon academic articles which assert that graffiti is often the ‘true’ voice of a community based on its ability to be expressed anonymously. Then he effectively applies such theories to the chicken-scratched scribblings on the UBC libraries’ desks to do exactly what our blogs are set out to do: provide critical case studies that color the more theoretical discussions gleaned from the class materials.

Riaz Makan’s blog (http://rmakan.blogspot.com/) makes a consistent and concerted effort to provide anecdotal, theoretical, and contemporary examples that both illustrate his own take on media functions and lend specific illustrative cases to the theoretical work done by other scholars. Principally, after reading the whole of the blog, Makan seems to be interested in cultural flows and subsequent remediation of foreign and local cultural capital through our own personal media creations. These discussions would appear to be informed largely by the writings of Walter Benjamin (“The Work of Art....”) and Arjun Appadurai (“Global Ethnoscapes...”). For example, in his post on the aboriginal use of radio to create community he is careful to delineate the difference in flow of mass culture and mass radio (i.e. one way, from station to listeners around the world) versus the interplay and truncated, regional flow of community radio stations such as CBQM. Furthermore, in his discussion of the “Jaan Pehechaan Ho” he traces levels of cultural “equivalence” between appropriate and inappropriate recreations of foreign media products (i.e. the songs and dances of Bollywood). His concerns are also traced through the “Jai Ho” post where he makes it clear that ‘why’ something is being remade is critical to its acceptance as well. In the modern age of global cultural flow we must take care not to simply remake things because they are popular or ‘fun’ but because we want to express some sort of deeper connection to the original medium.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

[We are] the Devil

Gordon Gray’s discussion of structuralist film theory, described in his book Cinema: A Visual Anthropology, asserts that the essential basis of structuralism is that we, as humans, look at our world through established sets of oppositional binaries (good/bad, left/right, land/water, etc.). The cinematic example he provides to better illustrate the relationships of such binaries to the world of film, is Star Wars; where Darth Vader is ‘bad’ and Luke Skywalker is ‘good.’ The simplicity of such a dichotomy (what structuralists define as a work’s ‘master antimony’ or central opposition), Gray suggests, is part of what made the film such a universal success.

South Korean director Kim Ji-Woon’s 2010 horror/thriller picture I Saw the Devil utilizes the same master antimony to drive the plot forward, good versus evil, but does so in a much more nuanced, complex, and, ultimately, disturbing way than we see in Lucas’s Star Wars. Whereas in a film such as Star Wars the action is driven by the fundamental opposition and battles between good and evil embodied by two specific forces (in Star Wars this is quite literally expressed), I Saw the Devil is more concerned with what Gray describes as ‘transitional zones’ where people, or characters, demonstrate both good and evil behaviors or attitudes and thus express the true complexity of human nature.

I Saw the Devil begins much like any other horror film, with a quiet road at night, where an unsuspecting, defenseless, and utterly innocent victim (in this case a young pregnant woman) is met by a ruthless, remorseless killer, Kyung-chul. Thus, we have, early on, the violation of what appears good by that which appears evil, and we, as the audience know where we stand: on the side of good and united against a vicious murderer. Thus, we identify with our film’s protagonist and the victim’s fiancé, special agent Soo-Hyun, who vows to bring the killer to justice.

At the moment of Soo-Hyun’s first encounter with Kyung-chul—who we, the audience, now know to be an utterly sadistic serial murder and rapist—we are ready to see the triumph of good over evil and watch an inhuman criminal be brought to a merciless justice. Much unlike the abhorrence felt during film’s previous gruesome murder scenes, we now feel a vengeful satisfaction as we watch Soo-Hyun brutally attack Kyung-chul and beat him within a hair’s breadth of his life. Then, Soo-Hyun stops. He breaks Kyung-chul’s arm, plants a tracking device on him and lets him go. Only to track him down again, beat him nearly to death again, cut his Achilles tendon, and, once again, release him. So the pattern continues, each time pushing the audience and the protagonist further away from their original position of moral authority. Yet, there is some level of viewing pleasure derived by the audience as we watch our protagonist slip into the role of a sadistic hunter and away from his earlier heroic position. We, much like Soo-Hyun, do not know where to draw the line between just punishment and sadistic, self-serving revenge.

At the end of the film, the audience’s position can best be described as one of ambivalence, even guilt, as we watch Soo-Hyun defy the police to exact revenge upon Kyung-chul. We are unsure whether we would prefer the violence to stop to watch Kyung-chul turn himself in (as he now plans to do) or if he should ‘get what he deserves’, a slow, painful death at the hands of Soo-Hyun. So our original, morally authoritative stance has now been completely destabilized by the blurring lines between vengeance and justice. It is no longer good versus bad, but, instead, it is the perpetuation of violence or the beginning of a vaguely unsatisfactory peace through lawful justice.

Source:

Gray, Gordon

2010 Film Theory. Cinema: A Visual Anthropology. 35-72.

South Korean director Kim Ji-Woon’s 2010 horror/thriller picture I Saw the Devil utilizes the same master antimony to drive the plot forward, good versus evil, but does so in a much more nuanced, complex, and, ultimately, disturbing way than we see in Lucas’s Star Wars. Whereas in a film such as Star Wars the action is driven by the fundamental opposition and battles between good and evil embodied by two specific forces (in Star Wars this is quite literally expressed), I Saw the Devil is more concerned with what Gray describes as ‘transitional zones’ where people, or characters, demonstrate both good and evil behaviors or attitudes and thus express the true complexity of human nature.

I Saw the Devil begins much like any other horror film, with a quiet road at night, where an unsuspecting, defenseless, and utterly innocent victim (in this case a young pregnant woman) is met by a ruthless, remorseless killer, Kyung-chul. Thus, we have, early on, the violation of what appears good by that which appears evil, and we, as the audience know where we stand: on the side of good and united against a vicious murderer. Thus, we identify with our film’s protagonist and the victim’s fiancé, special agent Soo-Hyun, who vows to bring the killer to justice.

At the moment of Soo-Hyun’s first encounter with Kyung-chul—who we, the audience, now know to be an utterly sadistic serial murder and rapist—we are ready to see the triumph of good over evil and watch an inhuman criminal be brought to a merciless justice. Much unlike the abhorrence felt during film’s previous gruesome murder scenes, we now feel a vengeful satisfaction as we watch Soo-Hyun brutally attack Kyung-chul and beat him within a hair’s breadth of his life. Then, Soo-Hyun stops. He breaks Kyung-chul’s arm, plants a tracking device on him and lets him go. Only to track him down again, beat him nearly to death again, cut his Achilles tendon, and, once again, release him. So the pattern continues, each time pushing the audience and the protagonist further away from their original position of moral authority. Yet, there is some level of viewing pleasure derived by the audience as we watch our protagonist slip into the role of a sadistic hunter and away from his earlier heroic position. We, much like Soo-Hyun, do not know where to draw the line between just punishment and sadistic, self-serving revenge.

At the end of the film, the audience’s position can best be described as one of ambivalence, even guilt, as we watch Soo-Hyun defy the police to exact revenge upon Kyung-chul. We are unsure whether we would prefer the violence to stop to watch Kyung-chul turn himself in (as he now plans to do) or if he should ‘get what he deserves’, a slow, painful death at the hands of Soo-Hyun. So our original, morally authoritative stance has now been completely destabilized by the blurring lines between vengeance and justice. It is no longer good versus bad, but, instead, it is the perpetuation of violence or the beginning of a vaguely unsatisfactory peace through lawful justice.

Source:

Gray, Gordon

2010 Film Theory. Cinema: A Visual Anthropology. 35-72.

Ab"original" Radio

In the modern era of mass media interconnectivity (as defined by interactive online publishing and social media tools like Facebook and Twiiter), the once prevalent media form of interactive, call-in radio has become a lesser part of how we create, imagine, and keep in touch with our communities. This is not the case, however, with aboriginal peoples of Canada and Northern Australia where radio stations and their shows (specifically “request-line” or “call-in” style shows) are integral to these groups’ ability to express and create their own communities and collective identities.

In the case of Fort McPherson, an Aboriginal-Canadian town well inside the Arctic Circle, the organic radio programming of their station, CBQM, provides a lens through which one might understand the principle values or characteristic of their community and, also, how they are using radio to extend and further shape such communal qualities. After viewing the NFB documentary on the station, the first apparent quality is its dedication to inclusivity. It is, very much so, listener created radio, from the local, bi-lingual DJs to the constant call-ins with dedications, requests, and direct messages to other members of the community. This latter characteristic, causes the station to operate more like a public switch-board than a traditional radio station. While they do play music and even have their own sort of political talk radio, most of the time they are using CBQM as a mouthpiece to invite friends over for tea, do some well-wishing to those they cannot get in touch with otherwise, and to advise other community members of things such as wolves in the area or ice thaws. This non-traditional form (at least from a modern North American perspective) is indicative of some of the communication difficulties inherent in living in such a remote locale. From what one can glean from the documentary, people in Fort McPherson do not use cell-phones and are not always in their homes either (whether they are out in trapping lodges, community centers, etc.). Thus—what one might imagine to be their only radio station—CBQM becomes the perfect way to reach someone or to post a mass bulletin. Much how modern communities of North America may share a person-to-person message with their entire community through something like a Facebook wall-post, so too the listeners of CBQM share similar messages in a similar fashion. This act of sharing messages is an integral reflection upon the inclusivity of the Fort McPherson community, while also being a practical solution to the communication difficulties present in the remote region.

The Aboriginal communities half-way around the world in Northern Australia are, interestingly enough, using radio in a similar manner to their counter-parts in Canada. Utilizing radio to connect with “rellies” (relatives) and to share with their communities. The major difference here, however, is the establishment of more comprehensive network not to simply to support connections within the community but to create links to other remote aboriginal groups across Australia. This makes their radio stations not only integral to their preservation of a self-defined community but also to their survival as a recognized political and ethnic group.

While neither of these stations seem overtly engaged in presenting traditional aboriginal programming (both, actually, seem to have a distinct affinity for country music of all kinds), they are still the mouthpieces of their distinctive groups and are capable of putting forth a new, more modern and perhaps more subtle aboriginal identity based on inclusivity.

Sources:

Allen, Dennis

2010 CBQM. National Film Board of Canada.

Fisher, Daniel

2009 Mediating Kinship: Country, Family, and Radio in Northern Australia. Cultural

Anthropology 24(2):280-312

In the case of Fort McPherson, an Aboriginal-Canadian town well inside the Arctic Circle, the organic radio programming of their station, CBQM, provides a lens through which one might understand the principle values or characteristic of their community and, also, how they are using radio to extend and further shape such communal qualities. After viewing the NFB documentary on the station, the first apparent quality is its dedication to inclusivity. It is, very much so, listener created radio, from the local, bi-lingual DJs to the constant call-ins with dedications, requests, and direct messages to other members of the community. This latter characteristic, causes the station to operate more like a public switch-board than a traditional radio station. While they do play music and even have their own sort of political talk radio, most of the time they are using CBQM as a mouthpiece to invite friends over for tea, do some well-wishing to those they cannot get in touch with otherwise, and to advise other community members of things such as wolves in the area or ice thaws. This non-traditional form (at least from a modern North American perspective) is indicative of some of the communication difficulties inherent in living in such a remote locale. From what one can glean from the documentary, people in Fort McPherson do not use cell-phones and are not always in their homes either (whether they are out in trapping lodges, community centers, etc.). Thus—what one might imagine to be their only radio station—CBQM becomes the perfect way to reach someone or to post a mass bulletin. Much how modern communities of North America may share a person-to-person message with their entire community through something like a Facebook wall-post, so too the listeners of CBQM share similar messages in a similar fashion. This act of sharing messages is an integral reflection upon the inclusivity of the Fort McPherson community, while also being a practical solution to the communication difficulties present in the remote region.

The Aboriginal communities half-way around the world in Northern Australia are, interestingly enough, using radio in a similar manner to their counter-parts in Canada. Utilizing radio to connect with “rellies” (relatives) and to share with their communities. The major difference here, however, is the establishment of more comprehensive network not to simply to support connections within the community but to create links to other remote aboriginal groups across Australia. This makes their radio stations not only integral to their preservation of a self-defined community but also to their survival as a recognized political and ethnic group.

While neither of these stations seem overtly engaged in presenting traditional aboriginal programming (both, actually, seem to have a distinct affinity for country music of all kinds), they are still the mouthpieces of their distinctive groups and are capable of putting forth a new, more modern and perhaps more subtle aboriginal identity based on inclusivity.

Sources:

Allen, Dennis

2010 CBQM. National Film Board of Canada.

Fisher, Daniel

2009 Mediating Kinship: Country, Family, and Radio in Northern Australia. Cultural

Anthropology 24(2):280-312

Thursday, March 17, 2011

Imitation is flattery but when is it a mockery?

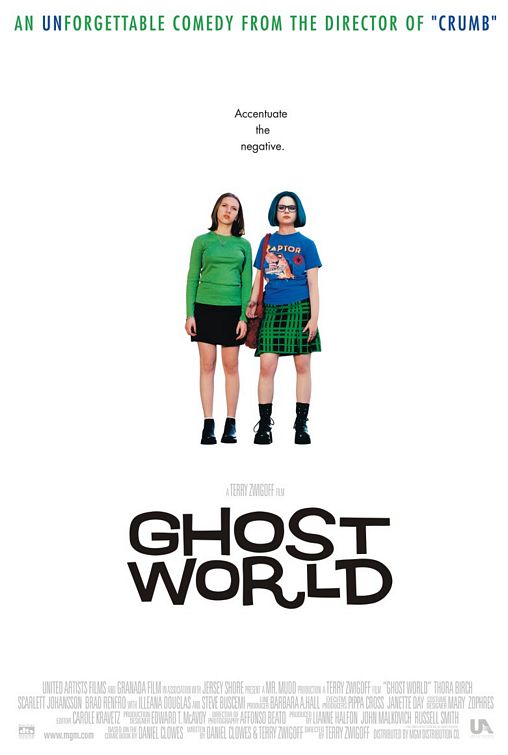

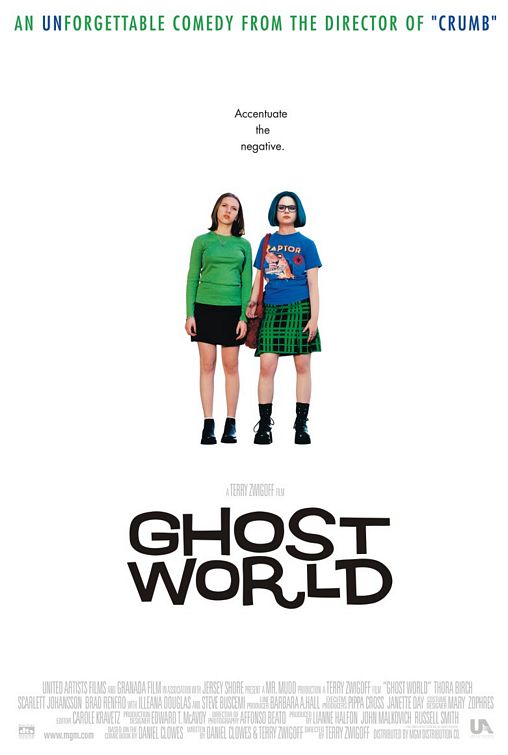

Prior to my reading of David Novak’s essay, “Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of Bollywood,” my own personal conceptions of appropriate versus inappropriate recreation or imitation of an original work—especially when crossing cultural lines—was based upon that slippery notion of authorial intent. A concept that one should consider through the lens of the work’s original artist, the lens of the person remediating the work, and through an analysis of the intended audiences of such performances of the final recreation. In other words, any amount of self-aware irony, devoted delicacy when dealing with foreign cultures, and an understanding on the part of the audience of such self-reflexive ironies, the transmutation of the foreign, and a semi-culturally-sensitive sense of humor could render a reification important and sufficiently ‘aware’ enough to be presented. The largely anecdotal argument presented by Novak’s article, however, asserts that the acceptability of certain recreations of the foreign through alternative cultural lenses are also heavily informed by cultural power relations.

Throughout the early segment of the article I found myself wondering, how is it that North American renditions of a Bollywood performance can easily be considered racist or ignorant while an Elvis impersonator in India is, so often, perfectly acceptable? According to Windy Chien (a protestor of a San Francisco group’s recreation of the Bollywood song/dance Jaan Pehechaan Ho, in Cantonese of all languages) it is the global cultural power difference between American media/culture and that of what must be considered a marginalized culture of Chinese-American and Indian. In other words, the majority of hegemonic cultural power may not engage in recreations or imitations of minority cultural forms no matter how self-aware or ironic the performers’ intentions may have been. The same way that our popular North American culture deems it acceptable for an African-American comedian to make fun of white people while the opposite (i.e. a white comedian making stereotypical claims about African-Americans for comedic effect) is inappropriate and racist.

Such black and white delineations (no pun intended) are obviously set up for failure, however, because they deny any concept of the individual’s right to express their own identity through irony or a self-aware assumption of what could be considered ‘foreign’ culture. By saying that no member of the majority may imitate any member or group of members from the minority for any reason is to implicate that majority member as 1) part of the majority based on ethnic lines (which could be labeled a form of racism unto itself) and 2) implicating them in any perceived wrongs perpetrated by the majority (i.e. white Americans may never imitate African-Americans due to a past discrimination of the part of their perceived ethnic group).

Thankfully, Novak’s article deals with the delicate nuances present in the arguments over appropriate versus inappropriate recreations of foreign cultural materials through his discussion of the film Ghost World in contrast to the San Francisco group’s performance. Here he discusses at length the importance of understanding people as individuals ensconced in a globalized/cosmopolitan culture where identity should not merely be understood as member of majority/minority groups but on a personal basis that often lies through consumption, assessment, performance, acceptance, and rejection of foreign and local cultural capital through different media channels.

Source:

Novak, David

2010 Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of

Bollywood. Cultural Anthropology 25(1): 40-72.

Throughout the early segment of the article I found myself wondering, how is it that North American renditions of a Bollywood performance can easily be considered racist or ignorant while an Elvis impersonator in India is, so often, perfectly acceptable? According to Windy Chien (a protestor of a San Francisco group’s recreation of the Bollywood song/dance Jaan Pehechaan Ho, in Cantonese of all languages) it is the global cultural power difference between American media/culture and that of what must be considered a marginalized culture of Chinese-American and Indian. In other words, the majority of hegemonic cultural power may not engage in recreations or imitations of minority cultural forms no matter how self-aware or ironic the performers’ intentions may have been. The same way that our popular North American culture deems it acceptable for an African-American comedian to make fun of white people while the opposite (i.e. a white comedian making stereotypical claims about African-Americans for comedic effect) is inappropriate and racist.

Such black and white delineations (no pun intended) are obviously set up for failure, however, because they deny any concept of the individual’s right to express their own identity through irony or a self-aware assumption of what could be considered ‘foreign’ culture. By saying that no member of the majority may imitate any member or group of members from the minority for any reason is to implicate that majority member as 1) part of the majority based on ethnic lines (which could be labeled a form of racism unto itself) and 2) implicating them in any perceived wrongs perpetrated by the majority (i.e. white Americans may never imitate African-Americans due to a past discrimination of the part of their perceived ethnic group).

Thankfully, Novak’s article deals with the delicate nuances present in the arguments over appropriate versus inappropriate recreations of foreign cultural materials through his discussion of the film Ghost World in contrast to the San Francisco group’s performance. Here he discusses at length the importance of understanding people as individuals ensconced in a globalized/cosmopolitan culture where identity should not merely be understood as member of majority/minority groups but on a personal basis that often lies through consumption, assessment, performance, acceptance, and rejection of foreign and local cultural capital through different media channels.

Source:

Novak, David

2010 Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of

Bollywood. Cultural Anthropology 25(1): 40-72.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)