Throughout the early segment of the article I found myself wondering, how is it that North American renditions of a Bollywood performance can easily be considered racist or ignorant while an Elvis impersonator in India is, so often, perfectly acceptable? According to Windy Chien (a protestor of a San Francisco group’s recreation of the Bollywood song/dance Jaan Pehechaan Ho, in Cantonese of all languages) it is the global cultural power difference between American media/culture and that of what must be considered a marginalized culture of Chinese-American and Indian. In other words, the majority of hegemonic cultural power may not engage in recreations or imitations of minority cultural forms no matter how self-aware or ironic the performers’ intentions may have been. The same way that our popular North American culture deems it acceptable for an African-American comedian to make fun of white people while the opposite (i.e. a white comedian making stereotypical claims about African-Americans for comedic effect) is inappropriate and racist.

Such black and white delineations (no pun intended) are obviously set up for failure, however, because they deny any concept of the individual’s right to express their own identity through irony or a self-aware assumption of what could be considered ‘foreign’ culture. By saying that no member of the majority may imitate any member or group of members from the minority for any reason is to implicate that majority member as 1) part of the majority based on ethnic lines (which could be labeled a form of racism unto itself) and 2) implicating them in any perceived wrongs perpetrated by the majority (i.e. white Americans may never imitate African-Americans due to a past discrimination of the part of their perceived ethnic group).

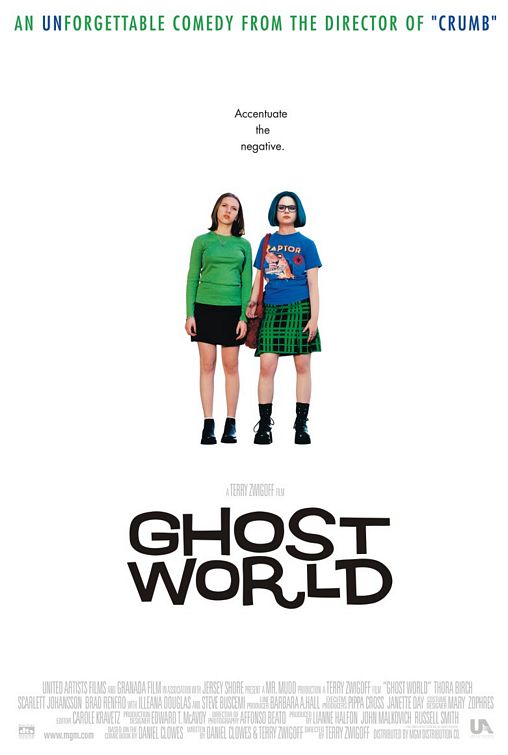

Thankfully, Novak’s article deals with the delicate nuances present in the arguments over appropriate versus inappropriate recreations of foreign cultural materials through his discussion of the film Ghost World in contrast to the San Francisco group’s performance. Here he discusses at length the importance of understanding people as individuals ensconced in a globalized/cosmopolitan culture where identity should not merely be understood as member of majority/minority groups but on a personal basis that often lies through consumption, assessment, performance, acceptance, and rejection of foreign and local cultural capital through different media channels.

Source:

Novak, David

2010 Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of

Bollywood. Cultural Anthropology 25(1): 40-72.

No comments:

Post a Comment